After a conversation with Ed Grebeck (Tempus Advisors), I thought it may be helpful to do a quick overview of the evolution of Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) from the “bubble” years to the current environment. The CLO market is the only securitization survivor of the financial crisis that has retained the full capital structure – from “AAA” down to equity (unrated tranche) and has fairly long maturities. The AAA tranches of the pre-crisis years were severely mispriced – paying as low as LIBOR + 23bp in 2007 for example – but came out of the crisis mostly unscathed (except in a couple of fraud cases).

Unlike their brethren in the CDO space that securitized sub-prime resi loans, the CLO collateral – portfolios of non-investment-grade corporate loans – experienced fairly modest default rates. The US corporate sector did reasonably well through the recession and was able to tap the HY bond market to refinance its debt or extend maturities (even for many weak credits). Some companies of course struggled and were too leveraged (like Clear Channel), sometimes undergoing debt restructuring (Tribune, Dynegy, etc.). Some firms, such as TXU – one of the largest LBO transactions to date – are yet to be restructured.

But even more importantly it was the diversification assumptions for the corporate sector that generally worked. Different industries were not impacted equally by the downturn. In the subprime mortgage space on the other hand, diversification was based on geography, a highly flawed approach. The rating agencies applied similar diversification assumptions/logic to California and Florida properties that they would to telecom and energy corporate sectors. The lesson was that corporate diversification, which has been employed by banks for centuries, works reasonably well but can not be translated into residential property markets based on geography.

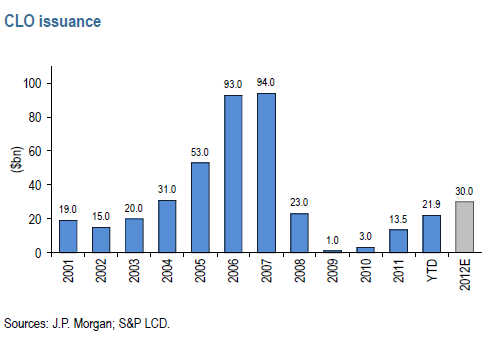

In spite of its relative success, the CLO market has changed markedly since the pre-crisis era. With no ability to use bank-backed commercial paper (ABCP) to fund the AAA tranches and no monoline (such as Ambac) guarantees, the AAA needed real investors. That means volumes, pricing, and leverage all needed to adjust. Volumes are of course a fraction of the bubble years these days, but are beginning to pick up.

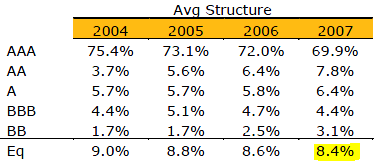

Leverage has also changed dramatically. The pre-crisis leverage kept increasing through 2007 as the equity tranche became “thinner”. 2007 leverage got as high as 15:1 (15x), averaging 12x (assets to equity).

That leverage dropped to 7.5x in 2010 as the rating agencies swung to the other extreme, taking the ultra-conservative approach.

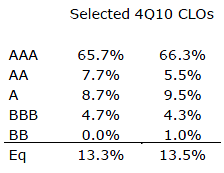

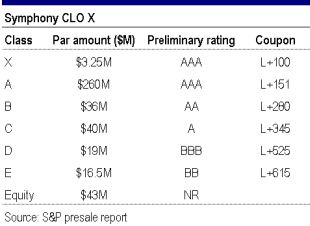

Leverage has increased somewhat since 2010. One of the deals that printed this month, managed by Symphony Asset Management and structured/distributed by Morgan Stanley, is leveraged just under 10x (417.75M total deal size over 43M equity tranche size = 9.7x).

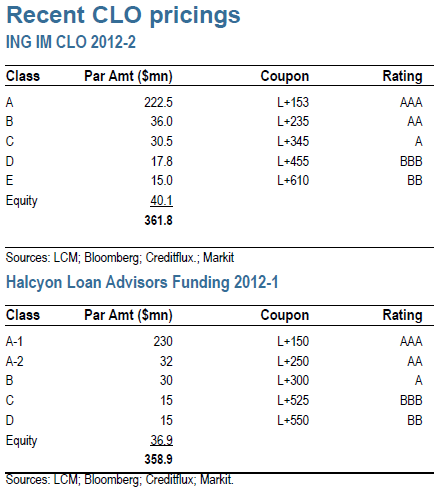

Note that the X tranche (78bp) represents Morgan Stanley’s fees as well as closing expenses (mostly legal and “warehousing” costs) which the bank financed for Symphony via the “super-senior” tranche. Pricing for the AAA tranche is now around LIBOR+150, making it a bit more interesting for institutional investors like insurance firms. Here are a couple of other recent CLO deal structures – both with leverage under 10x.

Other changes include permissible collateral. In 2007 CLOs permitted the inclusion of 5-10% of unsecured HY bonds and 5-7.5% of tranches of other CLOs. Up to 10% of second lien (as opposed to standard first lien) loans could also be included. Current CLOs generally do not allow any of this. Maybe a couple percent could be in bonds, but they would all have to be senior secured.

Legal maturities went from 12-14 years in 2007 to about 10 years these days. Perhaps the biggest change has to do with the “reinvestment period” – the period during which the manager is permitted to replace loans that prepay (partially or fully). It went from 6-7 years in 2007 to 2 years these days. Investors want the manager to build a portfolio and after a couple of years let the deal begin amortizing. That makes the AAA durations considerably shorter, reducing mark-to-market volatility.

CLO managers continue to be plagued by difficult markets. Low volumes of new institutional loans make it harder to ramp collateral quickly (a sufficient amount of collateral has to be invested in order to close the deal). At the same time banks do not finance loan “warehousing” for too long in fear of getting stuck with the collateral if the market shuts down and the deal does not close – which happened in 2008. Equity returns are considerably lower (because of lower leverage) than they used to be, ranging from 10% to 15% (vs. in the 20s during the pre-crisis era). New regulations pertaining to bank capital and risk retention rules will put a damper on how much the banks will be able to structure and distribute. And of course Europe could quickly bring this market to a grinding halt. Nevertheless as demand for fixed income stays strong (these days investors are chasing anything with a coupon), CLO managers are cautiously optimistic.